A Himalayan Paradise in Yorkshire

It’s considered one of the wonders of North Yorkshire... and rightly so. But the Himalayan Garden & Sculpture Park in Grewelthorpe, opened in 2005 just three miles south of Masham and five miles northwest of Ripon, is also one of the least known tourist attractions in the region.

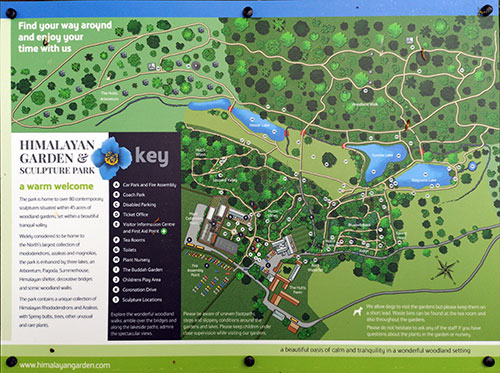

An open-air gallery – featuring some 80 contemporary sculptures, showcased in a tranquil valley-setting of some 45 acres of woodland, gardens and an arboretum – is enhanced by 3 lakes. It’s only open a few weeks of every year, but some 10,000 people make the pilgrimage annually.

The Himalayan Garden was winner of the Yorkshire in Bloom Award in 2018, showcasing as it does, some 1,400 rhododendron varieties, 250 azalea varieties and 150 different magnolias among its 20,000 plants. There’s even a newly planted 20-acre arboretum.

Peter Roberts – the man who was once the driving force behind the Golden Tulip hotel and PureGym chains – and his wife Caroline purchased the land in 1996 when it was little more than a coppiced hazel and spruce woodland. Peter was inspired by the hybrid rhododendrons which had been planted along the drive to the house, and started to research other rhododendron gardens in Colwyn Bay, Castle Howard, Cartmel and Cumbria. Following that, he made forays to the Himalayas to bring back to Yorkshire some of the native species there.

What makes this land so ideal for a Himalayan garden is, apparently, the acid soil, high rainfall and unique topography which creates numerous micro-climates.

Everywhere, particularly in late April and early May, rhododendrons and azaleas line the paths in a profusion of colour.

Not all the varieties have name tags, which is a shame if you are hell-bent on obtaining samples for your own garden, but as you turn every corner there is something else to smile about...

Dotted in often-unexpected places, and adding rather than taking away from the splashes of colour, are numerous sculptures – such as this ‘Thailand Hand’, by an unknown artist.

Close up, some of the flower heads are quite stunning...

To add to his extensive plant collection, every year Peter Roberts commissions new sculptures for the grounds.

Six of them by an Indian artist, Subodh Kerkar (the Founding Director of the Museum of Goa) are really attractive. His work is showcased all over the world, and Ghandi’s principle of ahimsa (doing no harm) is a theme that runs through his work.

The first of his sculptures you come across is called the ‘Cotton Tree’, and alludes to Yorkshire’s industrial heritage. A notice beside it tells us that cotton originated in India. Apart from spices, cotton was one of the major Indian export commodities. In 1350, an Englishman named John Mandeville, wrote a book called ‘The Travels’, in which he wrote about a tree in India that grew wool. "There grows in India a wonderful tree which bears tiny lambs on the end of its branches. These branches are so pliable that they bend down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungry”. Kerkar explains that he covered his cotton pods with patterns of crochet (a Portuguese knitting style) and one of the cotton pods is fitted with a lamb’s head.

Others of his sculptures show that the man has a good sense of humour as well as being highly creative. Take this ‘Book Tree’, for instance, that features logs carved with books encased in resin, symbolising the process from tree to book

Or how about ‘Logs of Dialogues’, a sculpture that consists of 18 logs painted with eyes and open mouths. Kerkar explains that he made it in response to the rise of terrorism. “Terrorism is a product of a lack of communication,” he says. “The world needs dialogue more than ever before.”

Yet another of his works, ‘The Ocean Comes to Yorkshire’, combines natural materials from Yorkshire with 10,000 shells shipped from his Goa homeland to chronicle Yorkshire’s ancient links with the sea. It features logs covered with cowrie and tower shells.

“When the Vikings came to Yorkshire they used the ocean as a highway. There are more than 2,000 place names in Yorkshire originating from that Viking culture. Cowrie shells were used as currency, because they didn’t disintegrate, and porcelain, named from the cowrie shell, was much prized in the UK,” he adds.

Other sculptures are also attractive, but in a totally different sort of way from those of Kerkar’s. Here’s something called ‘Slate Cone’, which can be seen from some way away and is made from embedding pieces of slate into a cylinder of concrete.

‘Fisherman’s Head’, by Christopher Marvell, doesn’t look a bit out of place beside one of the lakes.

And ‘The Swift’ by Hamish Mackie is elegant in its simplicity.

Looking forlornly over another of the lakes sits a sculpture that goes by the name of ‘Still Sitting’ by artist Helen Sinclair. Have you ever seen such a sexy bottom!

Adorning one of the lakes is a series of red-painted bridges, setting off nicely against a red sculpture that emerges out of the water a few hundred yards further on.

And recently added is a Norse ‘Stabbur’ – or store house – by local craftsman Paul Grainger. A Stabbur was typically built on wooden poles or tables of stone to ensure they were raised off the ground. By the end of the 9th Century there were large-scale settlements of Scandinavians in Britain and the densest Viking population was found in Yorkshire, where they had their capital city, York (Jorvik). Many Yorkshire dialect words and place names derive from old Norse owing to the Viking influence in this region.

Another building – a Kath Khuni (‘Kath’ means wood and 'Khuni' is corner, implying that the buildings should only have wood in the corners) adorns the arboretum area. In remote areas of northern India at altitudes of 4,500 to 7,000 metres, the inhabitants have a unique architecture, responding to the specific rural conditions, and in particular the frequent occurrence of large earthquakes. These buildings are made up of layered courses of wood and stone, topped off by a slate roof. The front of the house and balconies are then decorated with intricate wood carvings.

Traditionally the external walls are held together by wooden tenon-and-mortice joints rather than nails and are filled with rubble rather than cement, which allows the building to flex with Seismic waves and to disperse the destructive energy of earthquakes.

This Himachal Pradesh style of building uses cedar, stone and slate with Indian flagstones and the ornamental balcony (which is about 100 years old) was brought over from the region.

Opposite the Kath Khuni is a young oak, which was grown as an acorn from the Royal Vergelegen Oak in South Africa in 2010. This latter had been given as an acorn by the Duchess of Marlborough to Sir Lionel Philips in 1920 and sent to South Africa. It had come from the King Alfred's Oak at Blenheim Palace that is over 1,000 years old. So this oak is directly descended from both of them.

The magnolia’s flowering season is nearly over...

...as is that of the daffodils, narcissi and tulips...

But there is still a lot to enjoy, quite apart from the spectacular rhodies and azaleas.

But once your feet start feeling over-used, you can retire for refreshments in a Log Cabin tearoom, which serves a range of hot and cold drinks, and a variety of food options. Notice the blue-poppy logo which represents an extremely rare species that they have managed to cultivate here.

The ploughman’s lunch is excellent, and though there are one or two criticisms of the staff in this little restaurant to be found on the internet, I have to say that when we were there they couldn’t have been more friendly and with good service.

The Himalayan Garden is best visited by car, though it is also possible to reach it by taking buses 36 and then the 138A from Harrogate. Acklams Coaches also organise tours there.

Note that the gardens are only open for a few weeks each year, so check before you head off! In Spring they are open from mid April to mid July, while in Autumn they are open for most of October. 10am to 4pm Tuesday to Sunday and Bank Holidays.