Where did they put that Spit?

I don’t know what it is about aircraft that holds such a fascination for me. Maybe it was the fun time I spent working at Heathrow Airport; maybe it’s the amount of time I have spent sitting in airports around the world; or maybe it is the fact that all men love watching these objects of beauty and marvel that despite what the laws of physics say, you still feel a sense of awe that something so big and heavy can actually remain in the air at all.

Regular readers will know that I never waste a second looking out for new aircraft museums to go to – I think back with fondness to my visits to Beijing’s Civil Air Museum and Riyadh’s military air museum – but when my daughter suggested going to the RAF’s Cosford Museum on a recent trip back to the UK, it was a total non brainer of a question. With Lee and Genevieve acting as my chauffeur and companions, it surely promised to be a fabulous day out….

The Royal Air Force Museum at Cosford is located in Shropshire right next to an RAF base with an active airfield. It’s the sister museum of RAF Hendon down in London, and is the only place in the Midlands where you can get close up to so many breathtaking aircraft for free!

As you pull in to the car park (the only thing you actually have to pay for!) there’s a Bristol Britannia 312 (known as the Whispering Giant) parked nonchalantly by the side of the road. The RAF used 23 of these as transport planes. They could fly at 30,000ft and had a range of 8,545km; and as a front garden ornament, I guess they don’t come much better than this!

Over 70 aircraft of international importance are housed here and it really is amazing how much there is to drool over. “See the world’s oldest Spitfire and a Lincoln Bomber, just two of the highlights in the Warplanes Collection” reads the blurb. “The engine and missile collections total over 60 and are arguably one of the finest collections in the world,” it continues.

The whole museum is beautifully laid out and with so much to see you’ll feel like a kid in a sweetie shop (or perhaps how I felt when I was locked inside a bar inside a brewery and was told I could just help myself … but that’s a story for another day!).

Anyway, having parked, we were guided into a glass fronted Visitor Centre which (we are told) is fashioned in the shape of a bi-plane, though I think I would have been hard pressed to notice that at the time.

There’s not a lot to see in the visitors’ centre, save for a café and some much needed loos; oh, and the occasional missile suspended overhead…

but it’s main job appears to be to guide you in the right direction, such that as you emerge from its rear exit you get the first of your wow factors thrust into your face… in this instance a collection of three aircraft: a Hawker Siddeley Dominie T1 Crew Trainer, a Lockheed P2H Neptune 204 and a Hawker Siddeley Nimrod R1.

The Dominie is a multi-crew trainer that was in service from 1965-2011. It had a crew of six – one pilot captain and five students and instructors.

The Neptune was used for anti-submarine and reconnaissance work. It could fly up to 22,000ft and had a crew of 29! More than 110 built.

But for me without a shadow of a doubt, the Nimrod is the star attraction here. I have always loved it. It’s such a sexy plane! The original design was based on the de Havilland Comet and the MR1 Nimrod was remarkable in that it entered service ahead of schedule and on budget! (Doesn’t that say a lot about government procurement these days when such a comment stands out for being so unusual!)

Three Nimrods were modified for electronic intelligence gathering – intercepting electronic communications and radar transmissions. Their role was so sensitive that they weren't officially acknowledged until after the Cold War was over.

This particular Nimrod went into service as a maritime reconnaissance aircraft but was converted to EIG status after one of the other Nimrods was lost in an accident. It flew out of RAF Kinloss in Morayshire, Scotland, and RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus. In its upgraded R1 status it flew out of RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire. In May 2011 it carried out 91 days of service in Libya.

As one leaves this trio of planes, the path leads you to a hangar labelled Test Flight. They say that each advance in aircraft technology is as a result of a great deal of trial and error. This hangar shows aircraft that were built to test a particular new theory or line of research. Most of them, of course, were produced in secrecy, often borrowing components from other aircraft types. It’s a Frankenstein Hangar with amazing technologies thrown together to produce the most amazing aircraft the world has ever seen! These were the machines, of course, that helped Britain open new frontiers of flight and gave it such a reputation around the world.

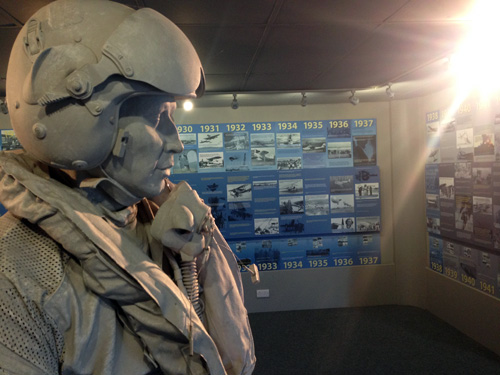

As you enter the gallery you’re presented with a timeline, shown in the context of world aviation and significant socio/economic historical events. Here are the Wright Brothers, for instance; or the Hindenburg disaster; Concorde’s maiden flight; the start of Jumbo Jets; and so much more besides… not forgetting, of course, that The Royal Air Force itself was founded in April 1918 by Lord Trenchard, who instigated the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps with the Royal Naval Air Service, making it the oldest independent air force in the world.

It is said that Lord Trenchard – who was born in 1873 – learned to fly at the age of 39 and was granted a pilot's licence after a grand total of one hour and fourteen minutes in the air!

Of course, before the advent of computers and sophisticated simulators, highly skilled pilots had to test fly each of these aircraft, many putting their lives at risk, often with tragic results. But through them it led to well known successes like the Hunter, Victor, Vulcan, Lightning and Concorde.

To my mind, one of the most stunning planes on display here is the Bristol 188. Built mainly of stainless steel, it was designed to investigate the effects of heat on aircraft structures at very high speeds. Nicknamed the 'Flaming Pencil', only two Bristol 188s ever flew, a third being used for ground tests.

Both Bristol 188s were powered by de Havilland Gyron Junior engines; the first British engine designed for sustained running at supersonic speeds. Experience gained with this engine was later applied to the Olympus engines which powered Concorde.

Although a maximum speed of Mach 1.88 was reached, this fell far short of the required Mach 2 performance they wanted; and this, combined with fuel leaks and an endurance of only 25 minutes in the air, led to the cancellation of the Bristol 188 project in 1964.

But here’s something that puzzled me. If they named it the Bristol 188, doesn’t that somewhat imply that Mach 1.88 was always going to be its maximum speed? Don’t you think they might have tried calling it the Bristol 200 and attempt to bring it to M2? Sounds like they were throwing in the towel a bit early, don’t you think?

But just look what a beauty she was, not just from the front, but with a super-sexy rear to boot! Oh yes. A real tart of a plane, if you ask me!

The next to catch my eye is not a beauty at all. In fact it makes me wonder if the designer leant too heavily on the warp key in Photoshop one day and then tried to cover up his mistake. Oh, OK pedants, so they didn’t have Photoshop in those days, but you know what I mean!

A much modified Meteor F8 fighter, the 'prone position' Meteor, was used to evaluate the advantages of coping with the effects of gravity while flying lying down. In the early 1950s the adoption of a prone position cockpit in future combat aircraft designs appeared attractive for two reasons. Firstly, such a configuration enabled the frontal area of the airframe to be reduced and therefore reduced drag. Secondly, aircrew can withstand greater 'g' forces if not sitting upright, which could be seen as a bonus, given the need for jet combat aircraft to manoeuvre at ever increasing speeds.

But in practice the difficulties of operating the controls of the aircraft outweighed the advantages. Following some fifty-five hours of flight testing it was concluded that the prone position concept was feasible, but only if absolutely necessary for aerodynamic reasons. The aircraft was never flown solo from the front cockpit. The development of special aviation clothing offered a simpler solution to the problem of counteracting 'g' forces and the prone position was abandoned.

Next call on my attention, given the time I spent in that abysmal firm BAe Systems (when I worked for them in Saudi Arabia… No, don’t get me started!) was the Panavia Tornado P02 swing wing fighter. In Riyadh I’d make the occasional foray into the high security repair hangar belonging to the Royal Saudi Air Force, where I would chat to the guys (mainly Brits) who were fettling these state-of-the-art war machines. So it was good standing face to face with an old ‘friend’ here in Cosford.

Capable of attacking in all weathers, day or night, the Tornado’s terrain-following radar combined with advanced flight control and navigation systems enable it to fly at tree top level at very high speed, penetrating enemy air defences to make conventional or nuclear strikes against key targets deep inside hostile territory.

The Saudis have a whole bunch of these fighters; and during the Gulf War it made low level attacks against Iraqi airfields with its specialist airfield denial weapon before moving on to medium level attacks using laser guided bombs against bridges, fuel depots and weapons dumps.

Flying at Mach 2.2 above 36,000ft, this 2-seater can carry eight 1000lb bombs, a JP233 airfield denial weapon, Paveway laser-guided bombs, Sidewinder air-to-air missiles and a nuclear weapon.

Next on my radar, and guaranteed to evoke high emotions even nowadays, the development of the British Aircraft Corporation TSR2 was one of the most exciting and controversial British combat aircraft designs of the 1960s. The cancellation of the project is still the subject of great debate.

During the mid 1950s, the RAF wanted a high speed, low level strike and reconnaissance aircraft to replace the English Electric Canberra. In October 1957, the Ministry of Supply released the first specification for such an aircraft. Eighteen months later the Ministry announced a design had been selected. The TSR2 (Tactical Strike and Reconnaissance Mach 2) aircraft was developed by a joint design team and a contract for eleven TSR2 prototypes was concluded on 6 October 1960. The first made its maiden flight from Boscombe Down on 27 September 1964. Initial reports indicated that the TSR2 was an outstanding technical success; but political opposition to the project led to it being cancelled from 6 April 1965. Puh! Politicians? Who needs them!

Beside the TSR2 stands a twin spool turbojet developed by Rolls Royce especially for it. It gave 30,610lbs of thrust.

And now another favourite. The first flight of P1 WG760 was on 4 August 1954, just 10 years after the RAF's first jet aircraft, the Meteor, entered squadron service. It was experimental and was the basis for the RAF's front line fighter, the English Electric (later BAC) Lightning. It was the first and only truly supersonic aircraft developed by Britain on her own.

In 1947 the proverbial back of an envelope design was so novel that the Ministry of Supply and the Royal Aircraft Establishment were deeply concerned as to whether it could succeed. Nevertheless, they placed an order for an experimental study. Two years later they placed a contract for two prototypes and an airframe for static testing. WG760, the first of the two prototypes, exceeded the speed of sound in level flight, achieving Mach 1.22. The second prototype P1A WG763 reached a maximum of Mach 1.53.

Further developments of the fuselage and the fitting of more powerful engines meant that later aircraft exceeded Mach 2.0. The Lightning stayed in service for nearly three decades.

Emerging from the Test Hangar, one steps out onto some tarmac where it appears the murder squad of the CID have been busy with their buckets of white paint, marking out the position of a corpse before it has been carted off to the morgue,

But what have we here? What kind of body was it?

In a clever bit of marketing, the Cosford team draws visitors in to a fenced off area devoted to the recovery of a Dornier Do 17 which was shot down into the shallow waters of the Goodwin Sands off the Kent coast. Two of its German crew were captured, while the bodies of the other two were washed ashore in Holland and England.

The Ministry of Defence, which is responsible for the investigation of all military aircraft crash sites in

the UK, only issued a licence for recovery of the Dornier because it was NOT a war grave. The aircraft is now on display at Cosford. It has been placed in two hydration tunnels where it is sprayed three times an hour with a citric solution, which helps prevent corrosion.

The next hangar to draw our attention is labelled The National Cold War Exhibition. In 2007, we are told, this £12.5 million project was opened at Cosford by Princess Anne. Many of the 19 aircraft inside are suspended in flying attitudes. Iconic cars, models, and audio visual hotspots tell the story of the Cold War in an innovative way. This, too, is the only place in the UK where you can see Britain’s three V Bombers: the Vulcan, Victor and Valiant.

After experiencing over 5 years of 'hot war' conflict in Europe, the Middle and Far East, there followed over 40 years during which the East and West stood either side of an ideological divide separated by the awesome prospect of nuclear holocaust; this was "The Cold War". In its initial years the Royal Air Force held Britain's nuclear deterrent through its 'V Force' and 'Thor' missiles… a deterrent that was later passed to the submarines of the Royal Navy. The National Cold War Exhibition highlights the ideologies of both sides, the social history of the era, the technological achievements which evolved from the competition between East and West and the eventual dissolution of the Warsaw Pact resulting in the world we live in today.

And upon entering, you realise that it’s not just aircraft that are packed into this hall. There’s a Centurion, for instance, introduced in 1945, as the primary British battle tank of the post-World War II period. It was such a successful tank design, that it saw service in the Korean War in 1950, in support of the UN forces. The Centurion later served in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, where it fought against US-supplied M47 Patton and M48 Patton tanks and they served with the Royal Australian Armoured Corps in Vietnam. Israel used Centurions in the 1967 Six Day War, 1973 Yom Kippur War, and during the 1978 and 1982 invasions of Lebanon. The Royal Jordanian Land Force used Centurions, first in 1970 to fend off a Syrian incursion within its borders during the Black September events and later in the Golan Heights in 1973. South Africa used its Centurions in Angola.

It became one of the most widely used tank designs, equipping armies around the world, with some still in service until the 1990s As recently as the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict, the Israeli Defence Forces employed heavily modified Centurions as armoured personnel carriers and combat engineering vehicles. South Africa still employs over 200 Centurions. Between 1946 and 1962 4,423 Centurions were produced, consisting of thirteen basic marques and numerous variants. In the British Army it was subsequently replaced by the Chieftain.

But we haven’t come to ogle at tanks. It’s the planes we are here for… such as the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 – the first Soviet fighter capable of flying faster than twice the speed of sound and an iconic aircraft of the Cold War years. MiG-21s saw extensive combat action in such diverse conflicts as Vietnam, the Arab-Israeli Wars, the Iran-Iraq War, Afghanistan and Desert Storm.

There’s also a MiG-15bis which had a better rate of climb, ceiling and high-altitude radius of turn than any Allied jet aircraft at the time. It came as a shock to the American pilots who first encountered it in combat over Korea.

Conceived in 1947, the design lacked a suitable engine until the British Government made a gift of an example of their latest turbojet, the Rolls-Royce Nene, to the Soviet Union. It was immediately stripped and copied and went into production for the new fighter and within eight months the prototype MiG-15 was flying, entering service in 1948.

By 1994 only the Cuban Air Force was still flying Soviet-built MiG-15bis aircraft, but several other Air Forces fly examples built in China.

And now another of my favourites – the English Electric Lightning F1/P1B, which I had heard so much about during my days in Riyadh when talking to ex-fighter pilots who now worked for British Aerospace, or BAe Systems as it became known.

The English Electric Lightning was capable of supersonic interceptions of enemy aircraft and it remained in front line service for nearly three decades. I remember one pilot describing it to me as akin to being strapped to a rocket. You were shot virtually into space and then came back to earth again and that was practically the duration of each flight!

The first P1B Lightning flew on 4 April 1957, the day the Government published a White Paper forecasting the end of manned aircraft and their replacement with missiles. As a result, several British military aircraft projects were cancelled, but the Lightning survived.

It was designed so that its armaments, radar and radio aids were integrated into the aircraft's flight and engine systems. The equipment were all as important as the aircraft's manoeuvrability and supersonic speed.

And as if that isn’t a feast for sore eyes, then what about the Hawker Siddeley Vulcan B2? The Vulcan was the world's first large bomber to employ a delta-wing form, offering a unique combination of good load carrying capabilities, high subsonic speeds at high altitudes and a long range.

The first production aircraft flew on 5 February 1955 and the second caused a sensation at the Farnborough Air Show by rolling during its demonstration.

The Museum's XM598 was selected as a reserve aircraft for the bombing raids on Port Stanley airfield during the Falklands campaign and on six occasions was airborne heading for the Falklands. It was never needed since the primary aircraft was able to carry out the raid alone. It was chosen because it had originally been built to carry the Skybolt stand-off bomb and it proved very easy to adapt to carry anti-radar missiles and an Electronic Counter Measures pod. The mountings for these are still fitted under the wings.

Meanwhile I always think you can’t beat a classic prop aircraft. One of the main attractions of the Riyadh air museum, for instance, is the Dakota which was given to the then King Abdulaziz by President Roosevelt. You can even climb on board there, something you unfortunately don’t get to do here in Cosford.

But Cosford has its own Dakota in the shape of a C47 which became the world's best known transport aircraft of its day. The type saw widespread use by the Allies during the Second World War and by Air Forces and airlines post-war. The DC3 first flew in 1935 and was ordered by America's airlines. With the outbreak of war these aircraft were diverted to the Allied Air Forces, followed by 10,000 military variants constructed before production ceased in 1946. Japan and the Soviet Union also built over 2,000 unlicensed copies.

There’s also a Handley Page Hastings which replaced the Avro York as the Royal Air Force's standard long-range transport from 1948. Two squadrons of the new aircraft served alongside the York throughout the Berlin Airlift, flying vital supplies into the city during the Soviet blockade. In fact it was a Hastings which made the last sortie of the Airlift on 6 October 1949.

This Cold War hangar never ceases to surprise with something to be discovered at every turn. Here’s a Hawker Siddeley Ikara ship-launched antisub missile, for instance. Its two stage solid fuel rocket engine carried an under-slung acoustically guided anti sub torpedo to the vicinity of an enemy sub where it was then released to attack the submerged target.

And another nice touch – a set of life-sized Matryoshka dolls, explaining the changing emphasis placed by Soviet presidents on the challenges of the Cold War, ending with the days of Perestroika and the eventual collapse of the Soviet empire.

Wow. There’s even a Trabant car that was an icon of the DDR, made by East German auto maker VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau in Saxony. With its poor performance, outdated and inefficient two-stroke engine, the Trabant is often cited as an example of the disadvantages of centralized planning. It was in production without any significant changes for nearly 30 years, with 3,096,099 Trabants produced in total.

I read somewhere that an S-class Mercedes produces the same amount of toxic waste over 30 miles that a Trabant chucks out in three seconds. As someone else so eloquently wrote, you should put one Trabant in a museum and shoot the rest!

Finally it’s time to leave the Cold War and instead head over to what is referred to as Hangar One, which is where they appear to throw in anything that doesn’t quite fit in to the other hangars. It’s home to the transport and training collection, as well as many engines and missiles.

I immediately fall in love with a Comet – such a sleek and beautiful construction as only such an iconic aircraft could be. The first flight of the Comet, the world's first jet powered airliner, took place on 27 July 1949. With jet engines and a pressurised cabin, it offered unprecedented levels of comfort and speed for its 36-40 passengers.

Unfortunately several disasters were to befall the Comet; in 1952 and 1953 there were take-off accidents and a Comet broke up in a violent storm over India. The next year the first production Comet crashed into the Mediterranean whilst en route from Rome to London. This was closely followed by a similar incident involving a Comet en route from Rome to Johannesburg, resulting in the withdrawal of its Certificate of Airworthiness. The cause was later found to be fatigue failure of the pressurised cabin.

Another beautiful aircraft – the Junkers Ju52/3M – stands close by. In its time, the Junkers was rivalled only by the Douglas Dakota as a transport aircraft. It was used by the airlines of thirty countries and several Air Forces. It was the last in a series of corrugated metal-skinned aircraft.

By 1934, the newly-formed Luftwaffe was flying bomber-transport Ju52s and the type was soon in action with the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion, which fought on the Nationalist side in the Spanish Civil War. In August 1936, Ju52s carried out what was then the biggest air-transportation operation ever mounted, carrying 14,000 of General Franco's troops from Morocco to Spain.

During the Second World War the Ju52 became the Luftwaffe's standard workhorse. Flown mainly as a transport, it also fulfilled air-ambulance and, more unusually, mine-clearance roles.

Hangar One is also where you come across a suspended Westland Wessex HC2. It’s a British turbine-powered variant of the American Sikorsky S-58, entering service in 1961. It was intended for transport, ambulance and general purpose duties, including carrying 16 fully-equipped troops or a 4000lb underslung load and ground assault with Nord SS-11 anti-tank missiles and machine guns.

I think it looks a little strange without its rotor blades, though no doubt the curators had their reasons for doing this.

The last RAF Wessex helicopters retired in 2003.

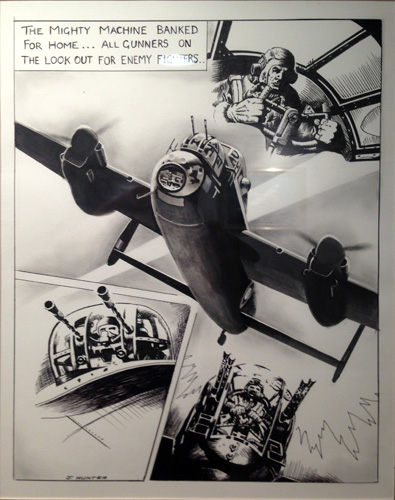

I mentioned that Hangar One appears where they put anything that doesn’t seem to fit in with other parts of the collection. One rather appealing side gallery is an art gallery put together by the Guild of Aviation Artists – a group founded in 1971 and now recognised throughout the world as the premier society for the promotion of aviation art.

The pictures here are all for sale and follow the lines that one has become familiar with over the years – the comic-book-hero drawing, for instance…

or the battles in the skies, so beloved of collectors after WWII…

Here’s one of the Battle of Britain salute with a Supermarine Spitfire and a Hawker Hurricane By Patricia Forrest …

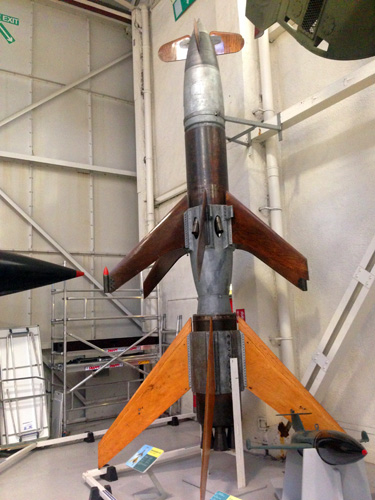

There’s also another side gallery for missiles, which overflows into the main hall, there being so many of them. Want to know what a German V1 looked like?....

Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 Germany was forbidden to manufacture heavy artillery, so it forced the German Army to consider the use of rockets for long range bombardment. In 1932 Army Captain Walter Dornberger was joined by the then 19 year old Wernher Von Braun. Together they developed a series of missiles leading to the development of the V2 in parallel with the V1.

A suitable rocket motor was not produced until 1940, and so the first successful launch did not take place until 3 October 1942. The first V2 fell on British soil at Chiswick at 6.43pm on 8 September 1944. Although some 10,000 A4s were produced, only about 3,000 were launched offensively.

Rheintochter was a German surface-to-air missile developed during World War II. Its name comes from the mythical Rhinemaidens of Richard Wagner's opera series Der Ring des Nibelungen. Starting in August 1943, 82 test firings were made. An air-launched version was also designed. But the project was cancelled on February 6, 1945.

We’re outside once more; and ahead of us is another icon of the skies: the Hercules.

First flown as a prototype for the United States Air Force in August 1954, the C-130 Hercules, as a troop transport, disaster relief and aerial tanker aircraft has been a mainstay of the RAF transport fleet since the late 1960s (along with those of many other air forces); it has seen extensive operational use including the Falklands, Iraq and Afghanistan.

This is a lumbering beauty that always looks good, even when she is having a bad hair day. Yes, she may look a bit overweight, but she’s still gorgeous!

We head on back to the visitor centre for a much needed stomach warmer at the café there. (It’s called Refuel, which I guess is as good a name as any.)

But hold on, a moment, one of us suddenly perks up. What happened to the Spitfire that the adverts bang on about so much? After a mutual conflab, we realise that no Spit was anywhere to be seen on our wanderings.

How could all three of us have missed out on seeing it? It’s only after a bit of head scratching and further investigation that we realise there is one more hall that we never even noticed!

Beyond the Test Flight Hangar there’s another called War Planes. But the traffic flow of F.O.D. (airport term for Foreign Object Debris, which I guess sums up the visitors to a tee) guides you right past the connecting tunnel and out towards the Dornier exhibit. Gingerly, we return once more along the path we began on and lo and behold almost the first thing we come across is a Supermarine Spitfire I – surely the most famous British fighter aircraft in history.

Nowadays I guess everyone knows that the Spit became a symbol of freedom during the summer months of 1940 by helping to defeat the German air attacks during the Battle of Britain. But maybe it’s the Spit’s positioning in the hall that could be to blame, but I have to say I find myself underwhelmed by it once we come face to face with it. It just looks so… ordinary compared with some of its companions

I mean – close by is a P-51D Mustang. The Mustang more than any other fighter wrested control of the skies over Germany from the Luftwaffe; combining a British designed engine and American airframe it was quite simply one of the best fighter aircraft built during the Second World War.

But it looks a pretty plane too!

As for the Catalina PBY-6A amphibian … It’s simply gorgeous! OK, I know I used to have a fluffy blue stuffed caterpillar called Catalina, and maybe that has clouded my judgement just a little bit, but I can assure you that this aircraft is well worth making friends with!

Even the de Havilland Mosquito TT35 is prettier than the Spitfire. OK, so it was made of wood and was used as an unarmed bomber, relying on its superior speed to escape enemy fighters (it was nicknamed 'The Wooden Wonder').

As for the big daddy of them all – the Avro Lincoln B2… well what can one say?

Just too late to see service during the Second World War, the Lincoln became the mainstay of Bomber Command post-war, but was destined for a short front line career as the Cold War and the jet age brought its shortcomings into sharp relief.

That Lincoln is an impressive plane, mark my words!

We exit the Warplanes Hangar and are surprised to see that despite an outside air temperature of some 11 degrees, they are leaving nothing to chance here, and have the bad weather notices standing by. But there definitely appears to be a paucity of snow, and certainly no gritters are out and about; so we head on back to the car park.

In summary I would have to say that without exception, this has to be the best aircraft museum I have ever been to. That overused epithet “something for everyone” must surely apply here. And with an entrance charge of £0.00 it also has to be one of the best value museums I have been to in a very long while.

Bye bye RAF Cosford! And thank you for a fascinating day out!